In our Trade Catalog Collection and in the Kibele and Garrard Architectural Records Collection we have some very interesting examples of Formica from the early to late 20th century.

It was created in 1910 by David J. O'Conor, an engineer at Westinghouse in Pittsburgh, who impregnated sheets of paper with the new invention liquid Bakelite. He had created a durable surface with insulating properties. A few years later, in 1913, O'Conor and Herbert A. Faber, another engineer, left Westinghouse in order to form their own company in Cincinnati to focus on this new invention.

Wondering about the name? Faber is credited with that: because it could stand in place for mica, an insulator that was becoming increasingly expensive at the time, the product officially became Formica. And it went on to cover kitchen counters around the world.

Images:

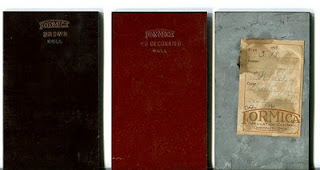

Formica samples, 1920s-30s, Kibele and Garrard Architectural Records Collection, Drawings + Documents Archive, Ball State University Libraries.

Formica trade catalog, TC 146, 1960s, Trade Catalog Collection, Drawings + Documents Archive, Ball State University Libraries